The superstition surrounding magpies, encapsulated in the rhyme “One for sorrow, two for joy,” remains a widespread belief, assigning fortune based on the number of magpies sighted. This article delves into the history, cultural context, and evolution of this enduring superstition.

The belief associating magpies with fortune has roots stretching back to at least the nineteenth century, where the quantity of magpies observed was interpreted as a direct predictor of future events. This practice stemmed from a longer verse, often recited as: “One for sorrow, two for joy, three for a girl, four for a boy, five for silver, six for gold, seven for a secret never to be told.” Although the poem does not explicitly name the magpie, it is widely understood to reference this particular bird, with the superstition occasionally extended to crows and other corvids in regions where magpies are less common.

This tradition has primarily been disseminated orally, resulting in numerous regional variations of the rhyme. In parts of America and Ireland, a different version is often recited: “One for sorrow, two for mirth, three for a funeral, four for a birth, five for heaven, six for hell, seven’s the Devil his own self.” The Manchester variation includes additional lines: “eight for a wish, nine for a kiss, ten for a surprise you should be careful not to miss, eleven for health, twelve for wealth, thirteen beware it’s the Devil himself.” These variations highlight the adaptability and enduring nature of the superstition within different communities.

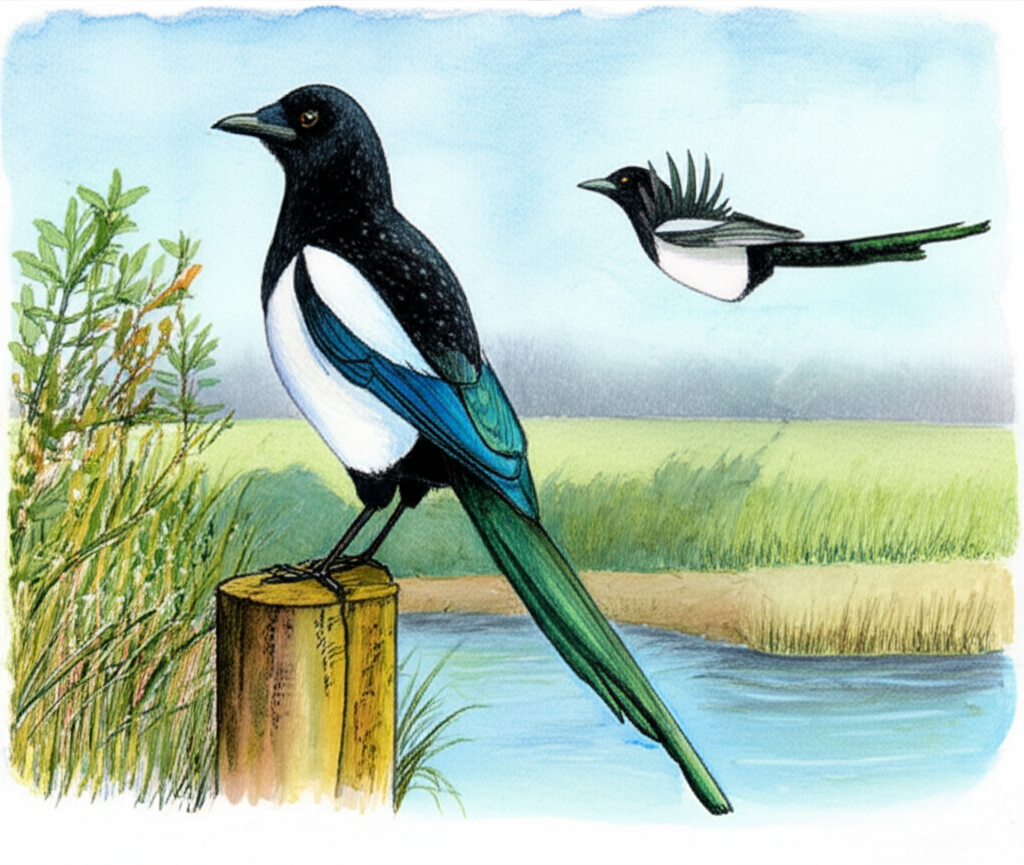

The references to the Devil within some versions of the rhyme offer insights into the superstition’s potential origins. Christian folklore suggests the magpie was the only bird that did not sing to comfort Jesus during the crucifixion, thus earning a negative association. Similarly, a Scottish legend claims that the magpie carries a drop of the Devil’s blood beneath its tongue. Beyond religious connotations, the magpie’s habits may have also contributed to its sinister reputation. Its tendency to steal shiny objects and prey on the chicks of other birds likely fostered negative perceptions among rural communities.

The sight of a solitary magpie was often considered a dire omen, foretelling great sorrow. To mitigate the perceived misfortune associated with a single magpie, various countermeasures have been developed over time. These include doffing one’s hat, spitting over the shoulder three times, and offering a salute to the bird. Another common practice involves greeting the magpie with the phrase, “Good morning, Mr. Magpie. How’s your wife?”, in hopes that acknowledging a second bird would counteract the impending sorrow with joy. The enduring nature of these practices reflects the persistent influence of this superstition in contemporary society.